What was life like in Minnesota during

the flu pandemic of 1918?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

Entering the third year of a deadly pandemic may have some Minnesotans wondering how things could possibly be worse. The final months of 1918 provide a sobering answer.

An influenza pandemic began ravaging the state in the fall of that year — ultimately killing more than 10,000 Minnesotans. Meanwhile, young men were being sent off to a bloody world war overseas and wildfires were destroying entire cities in northern Minnesota.

Reader Sarah Rasmussen moved into a 1917 Minneapolis home just before COVID-19 and realized they were not the first family to endure a pandemic within its walls. She wondered what life was like for those people a century ago.

"They may not have set up a small gym in the basement, but maybe they saw friends in the backyard," Rasmussen wrote in an e-mail.

She sought answers about life in Minnesota during the 1918 pandemic — and how it compares to today — from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reporting project fueled by great reader questions.

The deadly disease that began killing thousands in 1918 likely originated in Kansas, based on modern research. It quickly earned the nickname "Spanish influenza" because Spain was a neutral country in World War I and did not censor reports about the illness. After cropping up in military camps, it spread quickly due to the proximity and movement of troops during the war, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

By the fall, social activities in Minnesota ground to a halt much as they did in spring 2020. Some cities shut down schools and canceled large events. Police broke up crowds in local saloons. The University of Minnesota delayed opening for the fall semester.

"All the towns and cities for miles around are closed — everything but the meat markets, grocery and dry good stores," a young woman, LaVerne Roquette, wrote to her boyfriend overseas in October 1918. "At some places people have to wear gauze masks when they appear on the streets. … The government has closed all schools, churches, theatres."

"That was written 104 years ago, but could have been yesterday," said Curt Brown, author of "Minnesota 1918: When Flu, Fire and War Ravaged the State." A former Star Tribune reporter, Brown still writes a weekly history column for the newspaper.

Not everyone appreciated the precautions.

Dr. H.M. Bracken, executive officer of the state board of health, was vociferously opposed to the school and business closures in Minneapolis.

"If you begin to close, where are you going to stop? When are you going to reopen and what do you accomplish by opening?" Bracken told the Minneapolis City Council in October 1918. "Thus far, St. Paul has seen fit to follow my advice."

About 10 days later, citing a surge in cases, St. Paul followed Minneapolis in shuttering everything from churches and schools to soda fountains and bowling alleys.

Even government agencies were sparring over the new rules. The Minneapolis School Board tried to defy the city Health Department's closure order. The health commissioner responded by ordering the chief of police to close all school buildings and arrest anyone who tried to interfere. The schools, which had opened for half a day, were quickly closed again.

Poorly understood disease

The differences between the two pandemics largely outweigh the similarities, however, starting with the basic standards of living at the time. Cars were still a luxury item and home electricity wasn't guaranteed — particularly in rural areas.

"No one had radios in their homes. … They weren't getting barraged with total case numbers and death counts on social media and TV and radio," Brown said. "It was more word of mouth."

In Minneapolis, mail carriers and Boy Scouts were dispatched to homes and businesses to deliver placards and literature on the spread of influenza. Newspapers offered regular guidance, but there was limited understanding of the disease.

"Scientifically, they didn't even know what the influenza virus was until 1933," Brown said. "They thought it was bacteria."

The Minneapolis City Council ordered that the street commissioners "sprinkle and flush" the streets with water, because "the bacillus of Spanish influenza lurked in the dust of the streets," according to a Minneapolis Morning Tribune article from October 1918.

Some advice is familiar today. The assistant dean of the University of Minnesota medical school, Dr. Richard Beard, said at the time that the disease passed through particles "distributed by mouth or nose spray." To set an example, the Minneapolis Health Department eliminated the use of shared drinking cups and towels — and banned sneezing in the workplace.

The importance of fresh air was regularly stressed. Beard advised that people should open streetcar windows, work in ventilated offices, avoid crowded places and "sleep as nearly as possible out of doors."

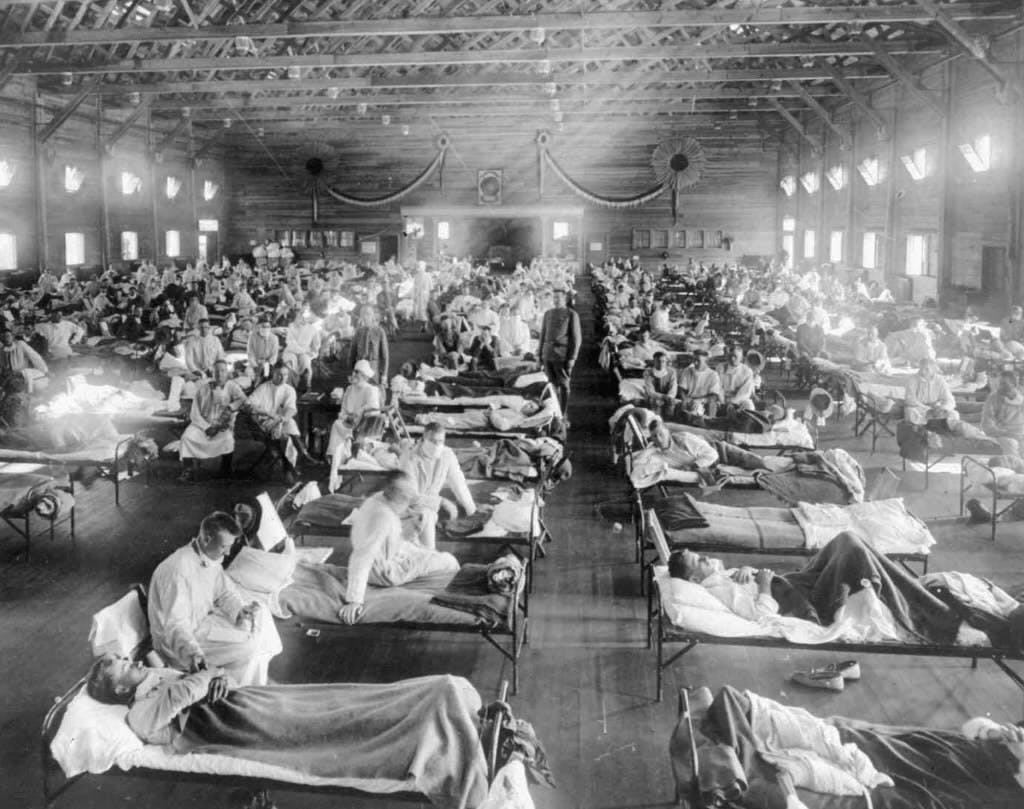

Hospitals overrun

Within weeks of the first case reported in Minneapolis, hospitals were overrun. U.S. Surgeon General Rupert Blue chastised the general public for relying too heavily on modern medical care.

"The present generation has been spoiled by having had expert medical and nursing care readily available," Blue said. "I believe the public generally ... has not interested itself sufficiently in studying the home care of the sick."

Testing wasn't available and treatment options were limited to prevention. It would be several decades before an influenza vaccine was available.

"There were no intensive care units or respirators," Brown said. "Death from disease was less of a mind-blow than it is today. I think they were used to people dying of diseases like diphtheria and smallpox."

Nursing staffs were stretched thin by the double crises of flu and war. Ambulances and hospitals in many cities were dedicated almost entirely to flu patients.

In early November 1918, half the nurses at the City Hospital (now HCMC) in Minneapolis were out sick with influenza, and substitutes were hard to find since many were helping the war effort or wildfire victims. Sailors from a naval training station in Illinois were called in to attend flu patients in Minneapolis.

Another place flu found fertile ground to spread was in the temporary housing set up for evacuees of the wildfires in northern Minnesota, says Brown. Historic wildfires in 1918 decimated entire cities and burned people and animals alive. Those who escaped the fast-moving blazes were packed into cramped housing or crowded hospitals.

'Trifecta of woe'

The flu lingered through 1919 and into 1920, though it claimed the majority of its victims at the end of 1918. As with our current pandemic, it came in waves that spurred lockdowns and subsequent re-openings.

When a shutdown was lifted in Minneapolis in November 1918, the Minneapolis Tribune reported that crowds quickly jammed movie theaters and dance halls.

"The passing throngs ... hesitated, still uncertain as to whether or not one huge joke was in the process of being perpetrated, walked up to the cashier's cage, and then, satisfied that it was all true, entered joyously," the Tribune reported about a movie theater.

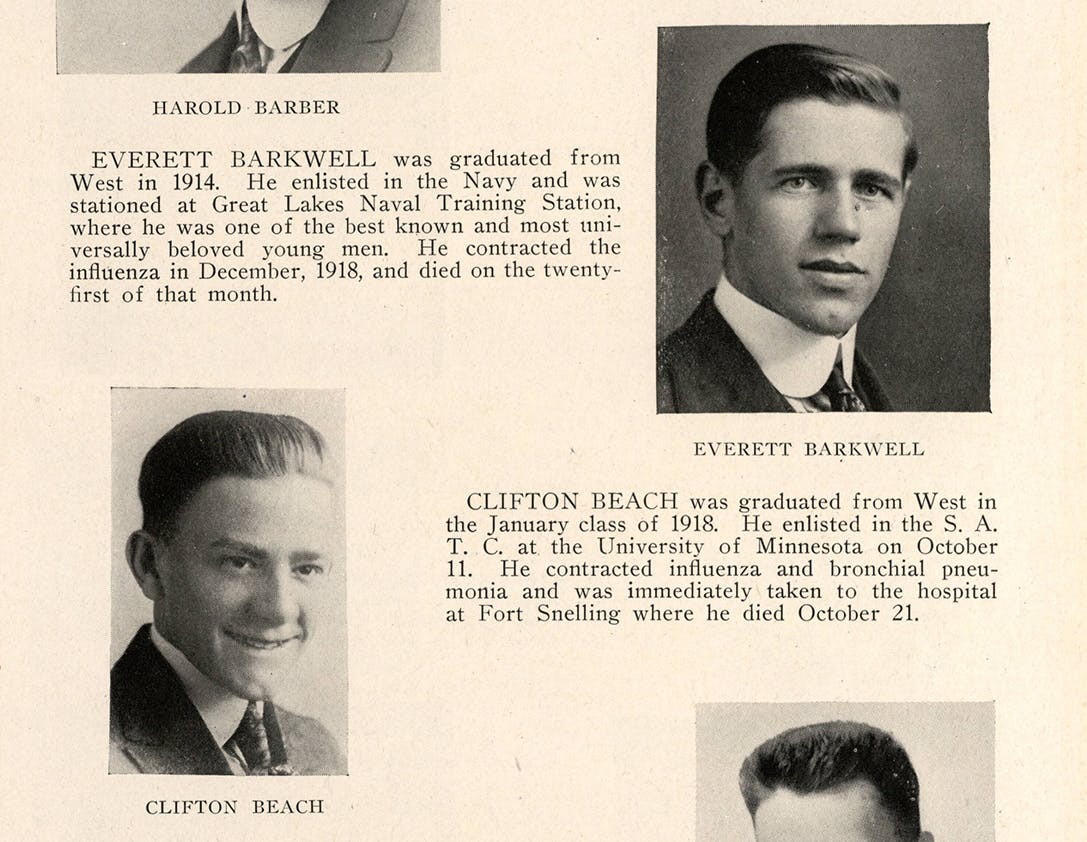

Roughly 12,000 Minnesotans ultimately died from the illness, Brown said, which is slightly more than have died so far from COVID-19. But Minnesota's population was less than half its current size, so proportionately the death toll was much larger. And unlike other outbreaks, an unusual number of healthy young adults succumbed to the 1918 flu.

"Then you throw on this huge forest fire in the fall and the guys serving in World War I," Brown said, "it was a trifecta of woe."