Every time Seth Snyder prepares a bottle for his 8-month-old son, he takes notice of the little packs of breast milk that he pulls out of the freezer.

The plastic storage bags at times bear the names of the women who expressed the milk. Some are friends; others are women Seth has never met. Many have carefully labeled the bags with time stamps of all hours of the day and night that they sat down to pump.

You've heard of meal trains. This is a milk train. More than 20 pumping mothers across Minnesota and as far away as California are donating their milk to feed this Minneapolis boy in honor of his mother's wishes. Neighbors on Seth's tightly woven block, still deep in their grief, can't help but smile when they refer to it as Project Milky Way.

"It hits me every day as I'm thawing these packets. It's not just getting a bottle ready," Seth tells me. "It's like I'm getting an act of love, often from a stranger."

These acts of love are also an outgrowth of the deep friendships his wife forged in every phase of her life.

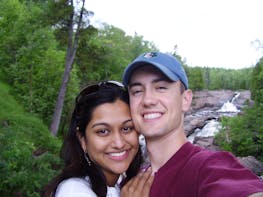

Radhika Lal Snyder was gregarious, brilliant, devoted, and "Type A-plus," Seth likes to say. Born and raised in India, she was a family medicine physician who specialized in maternal health. Part of her job involved looking after new mothers worn down by depression, until she died by suicide in July after struggling with her own postpartum mental health crisis. She was 39.

About one in seven women experience postpartum depression within the first year of giving birth. Far fewer — about one in 1,000 — suffer from postpartum psychosis, a dangerous mental disorder often marked by an impaired sense of reality. It's this rare condition that Seth believes haunted Radhika before she took her life.

The signs are evident to Seth only in hindsight, and he says they emerged suddenly. When he shows me pictures of Radhika snuggling with her babies — the couple also have a daughter who is now 9 — she seems to radiate with pride.

"Radhika was thrilled to be a mom," he says. "She was happy. She was just overcome by a serious brain disease."

On their tiny block, where a baby boom over the past decade has drawn families close, Radhika nurtured the neighborhood children as if they were her own. She gifted picture books to other brown kids featuring heroes that looked like them.

When one little girl crushed her toe after dropping a chair on her foot, a fully pregnant Radhika swooped in for a house visit and examination.

"My kids all still talk about her in such detail," says Heather Axtman, a mom of four who lives down the street. "She was my friend and such a gift to this world."

If the milk train has a conductor, Heather is it. She stores the milk, takes stock of supply and keeps the train running. The donations come from neighborhood friends, doctor friends, college friends, friends of friends, and complete strangers determined to help Radhika's family.

When women ask how much milk Heather can accept, she assures them it's as much as they can give. "I tell them my deep freezer is the size of my minivan," she says.

'A culture to bounce back'

Heather and Radhika both had pandemic babies. They were part of a close sisterhood of moms on the block who stayed connected through a group text while holed up in their homes. After Heather and Radhika gave birth, they talked daily about the joys of motherhood, the exhaustion of distance learning, the demands of breastfeeding and pumping — and the feeling of failing at everything.

"We wanted to be high achievers. We had more compassion and kindness for other people but such aggressive standards for ourselves," Heather says. "She was struggling with going back to work and the pressure we have as a culture to bounce back to normal."

Before Radhika died, Heather offered to give her some of her milk supply. Radhika said she would appreciate it.

It's important to point out here that Heather believes formula is a beautiful and necessary option. She chafes at the unfair pressure placed on moms to nurse their babies. But she says she feels driven to feed the Snyders' son until his first birthday because she believes it would have meant a lot to her friend.

"I would have given anything to have helped her more," she says, choking back tears. "When she died, a piece of my heart broke."

Signs of depression

When she was herself, Radhika commanded her orbit. The night Seth fell for her — they had mutual friends through their days at the College of St. Benedict and St. John's University — he was disarmed by her eyes, lively and vibrant. He sensed how keen and smart she was, and admired her quick comebacks that kept him on his toes.

Even before social media, Radhika kept close tabs on her friends across the world.

"One of our friends joked that she was a one-woman alumni association. You don't need a magazine — just call Radhika, ask her what other people are up to, and she'll give you the whole list," Seth says with a smile.

The first time he saw that light dimmed was shortly after she gave birth to their daughter nine years ago. She worried about how to dress the baby warm enough for a Minnesota winter. She wasn't sleeping much, and the Radhika who was always on top of everything seemed withdrawn and confused.

Seth came home one day to find her staring at the wall in silence.

"She admitted she was struggling, and she didn't feel she was a good mom, which of course wasn't true," recalls Seth, who at the time was in graduate school. "She didn't feel like she was doing enough to support me, to take stress off, so I could be a student, which of course wasn't true, either."

Seth called her doctor right away. With therapy and medication, and after accepting help from Seth's parents, Radhika was able to control her depression.

Not only that, Radhika got through medical school while raising a toddler. She gravitated toward maternal health because she thought the whole family should be cared for in the "fourth trimester" of pregnancy.

From her perspective, the medical system in the United States considered the mom's health paramount — until the baby was born. "Then suddenly, everything was about the baby's health," Seth says.

Radhika firmly believed that "every single new parent deserves to have the same focus on their health and well-being as the new baby," Seth says.

When their daughter was in grade school, Radhika was convinced that she and Seth should try for a second child. Although both were wary of her depression returning, this time, she reasoned, the circumstances would be different. They both had stable jobs and steady incomes. And they would aim for a spring baby, so she could enjoy walks with the newborn as the weather warmed up.

Clouds begin to lift

A bright-eyed baby boy arrived in late April. For those first several weeks, none of the old warning signs appeared. In fact, the Snyders felt a sense of hope: The COVID-19 vaccine was being rolled out and the outside world was starting to open up. The family began to see more of their friends. It felt like clouds were parting — until their son's two-month wellness checkup.

The baby's weight hovered near the 10th percentile, Seth recalled. The doctor encouraged the parents to supplement with formula. But the news sent Type A-plus Radhika down a self-destructive spiral.

Seth remembers her saying, "I'm not feeding him enough. I'm not taking good enough care of him. He's not getting enough sleep. I have to make him eat more so he will gain weight."

She began to forget important conversations and, over the course of a few days, seemed removed from reality. She would snap back to her normal self, but flashes of irrationality resurfaced. Out of the blue, she asked her husband, "Have I been an abusive spouse?" Seth recalled. " 'Am I pushing you to do too much? Did I push you to have a baby?' She was naming off this weird list of things that were obviously worrying her. And none of them were real."

That was one of the last conversations he had with his wife. She died the following day, on the Fourth of July.

'I was so confused'

We don't talk enough about how pregnancy and childbirth may lead to chemical and psychological changes. Combined with social pressures placed on new parents, especially during a pandemic, these changes can leave them in a world of hurt or in great danger.

"It's this whole combination of things, the perfect storm, that leads to severe depression, anxiety, and then eventual disconnection with reality, or psychosis," said Dr. Helen Kim, director of the Hennepin Healthcare Mother-Baby Program at the Redleaf Center for Family Healing.

Postpartum depression is common and treatable, she said. Postpartum psychosis is rare and a medical emergency. In both cases, symptoms can appear before the baby is born, so it's important to seek help before things get worse.

Early signs of psychosis may include the inability to establish what's true and not true. A person with this condition doesn't behave like themselves and may get stuck on an illogical train of thought.

"It can be subtle at first and then become more clear that someone is really psychotic," Kim said. "Another confusing sign of psychosis is that it can wax and wane," with periods of lucidity coming and going.

Before Radhika's funeral, Kim sat down to speak to Seth along with Radhika's parents. For the first time, Seth felt a sense of relief.

"I was so confused about how I could have lost the person that I knew so well and loved so deeply, so quickly without knowing that she needed help," he says.

But when he learned more about postpartum psychosis, he came to believe that Radhika didn't actively choose to kill herself. It was a disease, he realized, not a decision.

"It gave me permission to let go of some of that guilt for myself, or what I could have done differently."

Holidays and help

Now Seth and his daughter are confronting what Christmas will look like without Radhika. They are both receiving therapy. The children's squeals keep Seth going, as does a community of friendships that Radhika cultivated.

He worries that during this darkest time of the year, and nearly two years into the pandemic, families with babies will be hit hard this winter. Seth says he's sharing his story because while he didn't see the warning signs, maybe someone else who reads this will. He wants to help lessen the stigma surrounding perinatal mental health disorders and suicide.

And he thinks stories of resilience and community are important, too.

His neighbors and friends enveloped him those first several weeks when he simply could not function. His parents come every day to help with the baby. Heather and another mom on the block took his daughter back-to-school shopping. The dads swing by to hang out.

And every few days, he walks to Heather's house to fill up a picnic cooler of milk that nourishes his son.

"I don't know what I did to deserve this group of friends," he says. "This is the village Radhika built."

If you or a loved one is struggling with mental health during pregnancy or after childbirth, there are resources:

If you or someone you know is thinking about suicide, contact the Crisis Text Line by texting the word "HOME" to 741741. The U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is at 800-273-8255 (TALK).

A postpartum doula sponsorship has been set up in Radhika's name. Learn more about the program here.